ASF in the Americas is no science fiction at all

Provided that North and South America stay free of African Swine Fever, both continents could be having some profitable years. Very few remember that in the 1970s, the virus was already present there – leading to the culling of 1.2 million pigs at least. Pig Progress delved into the history books to learn more.

Click on country flag to go direct to information on that country.

|  |  |  |  |

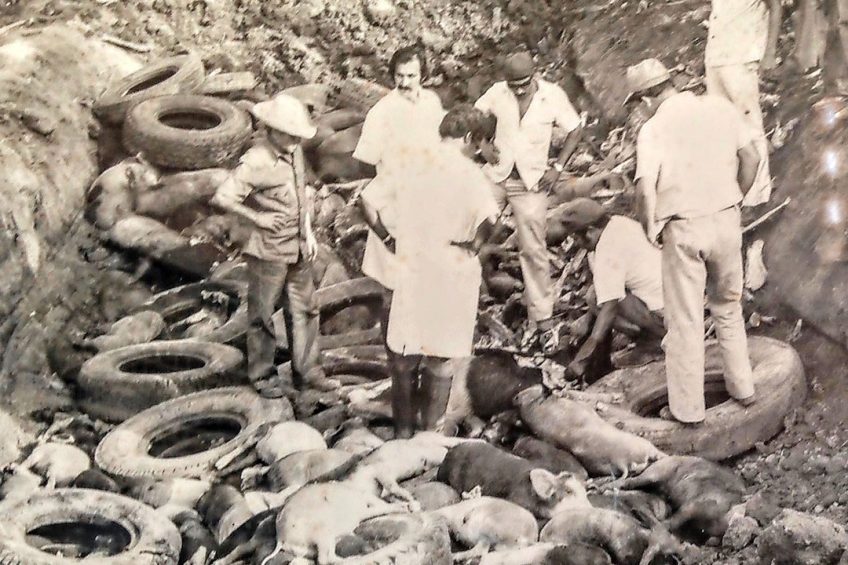

Dead pigs in a ditch, wood and tyres amongst them, and men around them ready to cremate it all. The image below could be a scene from Eastern Europe or Asia, in an attempt to limit the effects of a recent African Swine Fever (ASF) outbreak. The black and white of the picture, however, gives it away. This is not 2020 – this was more than 35 years ago. And it’s certainly not ‘East’. The picture is hanging in the Museum of the Revolution in Havana, Cuba.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, long before the current waves troubling Europe and Asia, and at a time when the virus was present in Africa and the Iberian peninsula, in a total of 4 countries in the Americas were confronted with ASF too: apart from Cuba (2x), these were the Dominican Republic, Haiti and Brazil. The result of Pig Progress’ history dive will be explained country by country.

3 conclusions jump out:

- When all documented cullings are added up, ASF caused at least 1.2 million pigs to die in the Americas, see Table 1.

- From this little literature review, it emerges that most likely there wasn’t just one introduction of the virus. One occurred in Cuba 1971, and 2 roughly simultaneously happened in the Dominican Republic and Brazil in 1978.

- Interesting in this context was how the virus travelled: by boat or by plane. In other words – it was humans who had brought the virus in.

So all in all, it may have happened a long time ago, an awful lot has been learnt about ASF ever since, and yes, oceans are a great biosecurity barrier. But it’s good to remember that the virus already managed to join humans on their travels to reach the Americas 3 times – and that that happened at a time when the world was not as connected as today.

The outbreaks are presented chronologically.

|  |  |  |  |

Cuba, 1971: Local depopulation

The outbreak of ASF in the area around Havana can be considered the odd one out, as it is the only one happening in 1971. First outbreaks were found on a finisher farm of over 11,000 animals on May 6, 1971, in Havana province. Acknowledging the virus’ risk for the  country’s 1.5 million pigs, the Cuban authorities took a strong and pro-active approach and opted for total eradication of pigs in both Havana province as well as Havana City province – provinces that have ceased to exist after a reorganisation in 2010. An overview by researcher Rosa Elena Simeon-Negrín and others (2002) described Cuba’s pig business in 1971 as “a new, well-structured industry with an important concentration of pork production in Havana Province and the western region of the country.” She describes how, with the help of civilians, movement of pigs was efficiently restricted, a census of pigs was organised and that the foci of ASF were eliminated by means of hygienic sacrifice.

country’s 1.5 million pigs, the Cuban authorities took a strong and pro-active approach and opted for total eradication of pigs in both Havana province as well as Havana City province – provinces that have ceased to exist after a reorganisation in 2010. An overview by researcher Rosa Elena Simeon-Negrín and others (2002) described Cuba’s pig business in 1971 as “a new, well-structured industry with an important concentration of pork production in Havana Province and the western region of the country.” She describes how, with the help of civilians, movement of pigs was efficiently restricted, a census of pigs was organised and that the foci of ASF were eliminated by means of hygienic sacrifice.

Simeon-Negrín wrote that in total, the Cubans identified 33 outbreaks in the two provinces. In total, this area included 463,332 pigs, she wrote, which all had to be eliminated. She added, “Private owners in both provinces were allowed to slaughter from three to five pigs for self-consumption and were required to sell the remaining animals to the state.”

Interesting remains the question as to how the virus managed to get onto the island. For that, it is good to bear in mind that Cuba, because of the language and history, still had commercial relations with Spain. On the Iberian peninsula, for decades there had been African Swine Fever. It is most likely, as Raymond A. Zilinskas presented in a review in 1999, that the virus came with contaminated food scraps from a Spanish aircraft.

Dominican Republic, 1978-1980: Total eradication

Around the outbreak of ASF in the Dominican Republic, there are various question marks. First: the moment of entry. Officially the outbreaks were confirmed in the west of the country in August 1978, but when counting back,  pigs had already started dying in January 1978. Equally unclear is the where of the first outbreak. Given that on other occasions mentioned in this overview, the virus came in through a major (air)port city, it looks likely that in this case the capital Santo Domingo might have been the port of entry. Just like in Brazil (to be published Monday 13th January), in the Dominican Republic a diversified picture could be seen in terms of virulence.

pigs had already started dying in January 1978. Equally unclear is the where of the first outbreak. Given that on other occasions mentioned in this overview, the virus came in through a major (air)port city, it looks likely that in this case the capital Santo Domingo might have been the port of entry. Just like in Brazil (to be published Monday 13th January), in the Dominican Republic a diversified picture could be seen in terms of virulence.

The Dominican Republic had a fair share of commercial farming. The country, occupying more than half of the island Hispaniola, opted for total eradication of the estimated 1.4 million pigs on the Dominican side. That didn’t mean that all of them in effect had to be culled. Some that still looked OK were sent to slaughter, whereas others died of the virus. In the end, 374 different foci had been found, and over 192,000 animals were culled, according to an overview edited by P.J. Wilkinson of the Animal Virus Research Institute, UK in 1981. This cost the Dominican authorities US$ 8.5 million. In 1981, the country was declared free from ASF.

One thing remains to be addressed. The virus also entered Brazil in 1978. However, there isn’t much evidence suggesting that there was a link between the two. As Franz C.M. Alexander pointed out, in 1978 there was not a lot of meat trade with the continent and the Dominican Republic due to Foot-and-Mouth Disease. More probable is that the Dominican Republic and Brazil got infected relatively simultaneously from the Iberian peninsula.

Brazil, 1978-1981: Targeted eradication

Arguably the best documented case is what happened in Brazil in 1978 and 1979. On Floresta farm near Paracambi, about 1 hour’s drive from Rio de Janeiro, pigs started dying as from mid-April 1978. At first, the owner did not think much of it and business carried on  as normal, which meant that animals continued to be sold off. In a review by J.A. Moura (2010), it is described how a South African veterinarian, while visiting the farm, suggested it might be ASF and had samples sent to a lab.

as normal, which meant that animals continued to be sold off. In a review by J.A. Moura (2010), it is described how a South African veterinarian, while visiting the farm, suggested it might be ASF and had samples sent to a lab.

Once confirmed, a big query was started up into where the animals had been sold to. Following the tracks, it turned out that the virus had spread to 224 locations in 18 states of Brazil – a country which had roughly 34 million pigs at that time. That included other farms but some animals had also ended up in poorer areas of the city of Rio de Janeiro. 5 states reported over 20 places to be positive for ASF – that included the pig states Paraná and Santa Catarina, but also São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Pará, in the north of the country.

An emergency plan was put in place, as described by ASF expert Dr Tânia Maria de Paula Lyra in various articles. A stringent approach led to the culling of almost 67,000 pigs at a cost of US$ 1.8 million. Unlike in Haiti or the Dominican Republic, however, the Brazilian authorities opted for a targeted rather than a total approach. Moura reported that also in 1981 a few positive samples returned from the lab, bringing her total count to 231. It was, however, the last to be heard of ASF in Brazil, as the government’s approach proved successful. On September 9, 1983, the country was officially declared ASF-free.

Worth noting is that ASF in Brazil showed a variation in virulence. In some places, the virus appeared to lead to 100% mortality, whereas in other places, lower mortality was observed. In this context it is good to point out that the Brazil virus was of genotype I, unlike the current outbreaks in Asia and Europe (genotype II). ASF expert Dr Mary Louise Penrith, located in South Africa, commented to Pig Progress, “There is a lot of speculation as to whether the variation in virulence observed in Brazil might have been due largely if not entirely to pig factors. Many of the pigs were in very poor condition and this can affect expression of the virus.

“Secondly, before and during the outbreaks in Brazil pigs were vaccinated with a CSF vaccine and it was speculated that although that would provide no specific protection against ASFv it may have boosted a non-specific immune response that altered the response of the pig to the infection.”

Last but not least – where did the ASF outbreak come from? The owner of the pig farm was also working at the nearby located Rio de Janeiro airport, which had just opened a new terminal. One, as Dr De Paula Lyra explained, at the time did not have an incinerator for left-over food brought from Europe. The owner simply brought home leftovers from planes from Portugal and Spain (where also genotype I was present at the time), and mix these with the pig feed rations. On his farm, the scraps were found, complete with cutlery indicating airline origin.

Haiti, 1978-1983: Total eradication

As the Dominican Republic share the island of Hispaniola with Haiti, it may not come as a surprise that the virus also travelled across the border to Haiti. First animals started dying in the Artibonito Valley, running east-west in the middle of the Hispaniola island, in the fall  of 1978. By then it was clear what danger it was, and a large part of the pig’s population started dying – some sources mention about two-thirds of the country’s population. That is mostly because, unlike the Dominican Republic, most pigs were kept in family conditions, i.e. under poorly developed circumstances.

of 1978. By then it was clear what danger it was, and a large part of the pig’s population started dying – some sources mention about two-thirds of the country’s population. That is mostly because, unlike the Dominican Republic, most pigs were kept in family conditions, i.e. under poorly developed circumstances.

Just like in the Dominican Republic, it was clear that total eradication of the pig herd would be the way to go. Haiti had roughly 1.4 million pigs at the time (also the current figure), it was also not a particularly rich country. In addition, other North American countries, afraid of the virus hopping from Haiti to the mainland, acknowledged the potential hazard and stepped in to have the eradication paid. Canada, Mexico and the USA therefore jointly paid for the eradication. To that goal a special programme was introduced, called the Project for Eradication of African Swine Fever and of the Development of Pig Production, better known by its French abbreviation Peppadep. In total over 384,000 pigs had to be culled at a cost of US$ 9.5 million, wrote Franz C.M. Alexander of the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States, Jamaica, in 1993. Haiti’s president declared the country free from ASF on April 28, 1982; Peppadep was closed in 1983.

The effects of the eradication were long-lasting, as repopulation took years. On top of that, an unforeseen side-effect was the extinction of a typical Haitian pig breed, being the Creole pig, a landrace that was well-adapted to local conditions. In recent years, there have been attempts to re-breed this type of pig which is similar to the Creole pig.

Cuba, 1980: Local depopulation

For the completion of this overview, this article returns to Cuba – the only country in the Americas that faced an outbreak of ASF twice. After the eradication in 1971, the virus  popped up in 1980 again on the other side of the island, in the easternmost provinces Guantánamo, Holguín and Santiago de Cuba. In total, 56 outbreaks were found. Cuba, having 1.4 million pigs in 1980, opted for a similar approach as in 1971 – and went for a total depopulation in the 3 affected provinces, culling 137,000 pigs. An adequate approach, if the official figures are to be believed. In August 1980 the virus had already disappeared.

popped up in 1980 again on the other side of the island, in the easternmost provinces Guantánamo, Holguín and Santiago de Cuba. In total, 56 outbreaks were found. Cuba, having 1.4 million pigs in 1980, opted for a similar approach as in 1971 – and went for a total depopulation in the 3 affected provinces, culling 137,000 pigs. An adequate approach, if the official figures are to be believed. In August 1980 the virus had already disappeared.

Cuba’s leader, Fidel Castro, pointed to the CIA, stating that it had been biological warfare. In this context the view of researcher Raymond Zilinskas matters. He pointed out that this type of reaction by the Cuban authorities was fairly common with all kinds of outbreaks happening in Cuba. Zilinskas even found a different explanation, given by Fidel Castro himself in 1980. It sounds like a more probable reason as to how the virus had arrived in Cuba in 1980.

He wrote: “We think it is probably attributable to a phenomenon that has been growing over recent years, and which is the dozens of boatloads of Haitian immigrants that have set out for the Bahamas, for the United States and other parts; and in come these boats, often in bad shape and without fuel. Some of them have even been shipwrecked. They lie off the north coast and the south coast. Sometimes they’d be carrying live animals and food, etc., and given the health conditions of the country that’s a risk even to public health.”

Click on country flag to go direct to information on that country.

|  |  |  |  |

Special thanks to Dr Cesar Corzo, University of Minnesota; Luc Willekens, HoCoTec; Daniel Azevedo Duarte, correspondent; Dr Tânia Pereira Freitas, Lanagro; and Dr Kyoung-Jin Yoon, Iowa State University. The article is summary of a Pig Progress presentation at AveSui EuroTier South America, July 2019.