Dynamics in China’s meat production, 2017-2023

African Swine Fever (ASF) and Covid-19 had a far-reaching impact on China’s meat production and trade. In 2 papers, Pig Progress examines the impact of ASF and Covid-19 on meat production, consumption and trade and the prospects for the next decade. This first article looks at changes in livestock numbers, meat production and meat consumption.

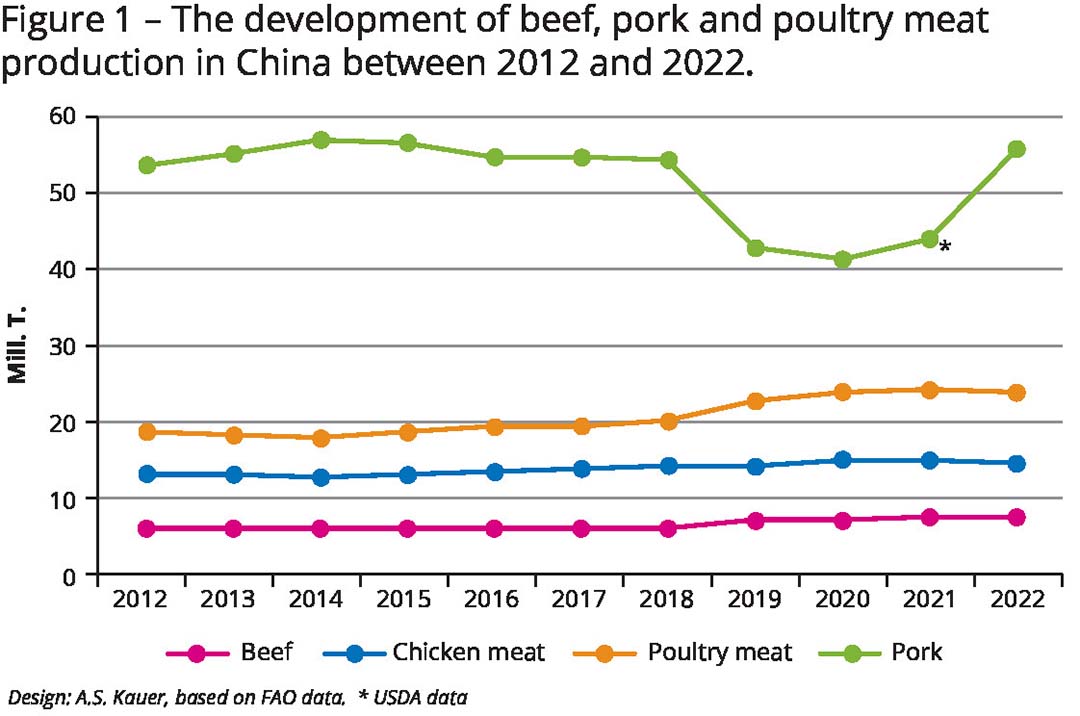

Between 2017 and 2023, the production of beef, pork and poultry meat developed very differently in China. Figure 1 shows that the production of beef has risen continuously and reached its highest level in 2023 with a relative increase of 25.7%.

In contrast, the production of pork decreased by 13.4 million tonnes or almost 25% between 2017 and 2021 due to the ASF outbreaks. It rose again in the following years to a level that was still 1 million tonnes below that before the outbreaks. The value reported in the FAO database for 2021 is far too high. It was replaced by data from the US Department of Agriculture (USDA). At 4.4 million tons, poultry meat recorded the highest absolute growth. It corresponded to a relative increase of 23.4%. However, a comparison with the development of chicken meat, which only increased by 1 million tons or 7.7%, shows that the growth was obviously mainly in duck and goose meat.

Change in meat production

The change in meat production between 2017 and 2022 also had an impact on China’s share in global meat production (Table 1). The ASF outbreaks resulted in a significant decline in pork in particular. The shares in beef and poultry meat increased. The decline in poultry meat in 2021 and 2022 will be discussed later.

Impact of ASF on consumer behaviour

A comparison with the development of domestic consumption shows very impressively the impact of ASF on consumer behaviour (Table 2). The willingness to buy pork obviously decreased during the peak phase of the outbreaks (September-December 2018). In addition to the high prices, a consequence of the reduced supply, uncertainty among consumers regarding the transmissibility of the disease to humans also contributed to this. This was exacerbated by the rapid spread of the Covid-19 virus. The lockdown of entire cities and the limited mobility of the population led to a decline in meat consumption.

Drastic increase in shortfall in pork supply

The result was an increased focus on poultry meat, which was significantly cheaper. Worth noting is the drastic increase in the shortfall in pork supply between 2019 and 2021 and in beef from 2019 onwards. In contrast, the deficit in chicken meat remained fairly stable over the entire period. Due to the importance of pork in terms of supplying the population and also in foreign trade, its dynamics are analysed in more detail below.

ASF: Decline in pig inventories

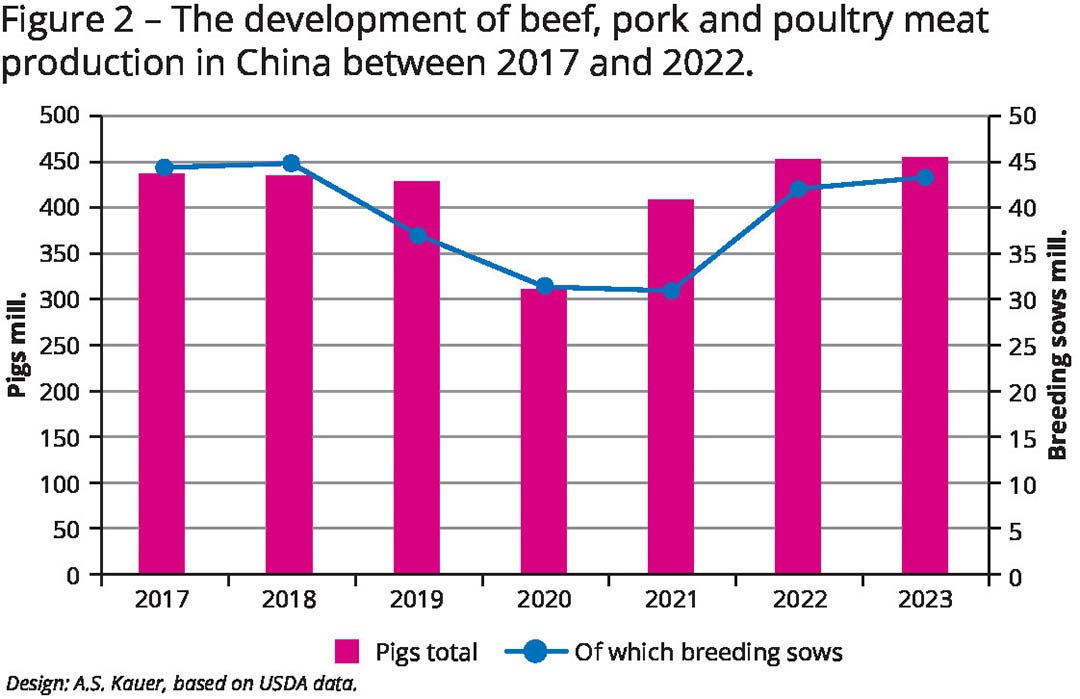

The first outbreaks of ASF were officially confirmed in August 2018. By the end of 2019, the highly infectious disease had spread throughout China. Figure 2 shows the development of the pig inventory as a whole, and that of breeding sows. Between 2017 and 2020, the number of pigs kept fell by almost 125 million, corresponding to a decline of 28.6%, reaching its lowest point in 2021. At the same time, the number of breeding sows fell by 13 million or 29.5%, reaching its lowest level in 2021. When the number of breeding sows recovered to 43 million in 2023, pig inventories also rose again, reaching 452.6 million in 2023, 4% higher than before the ASF outbreaks began.

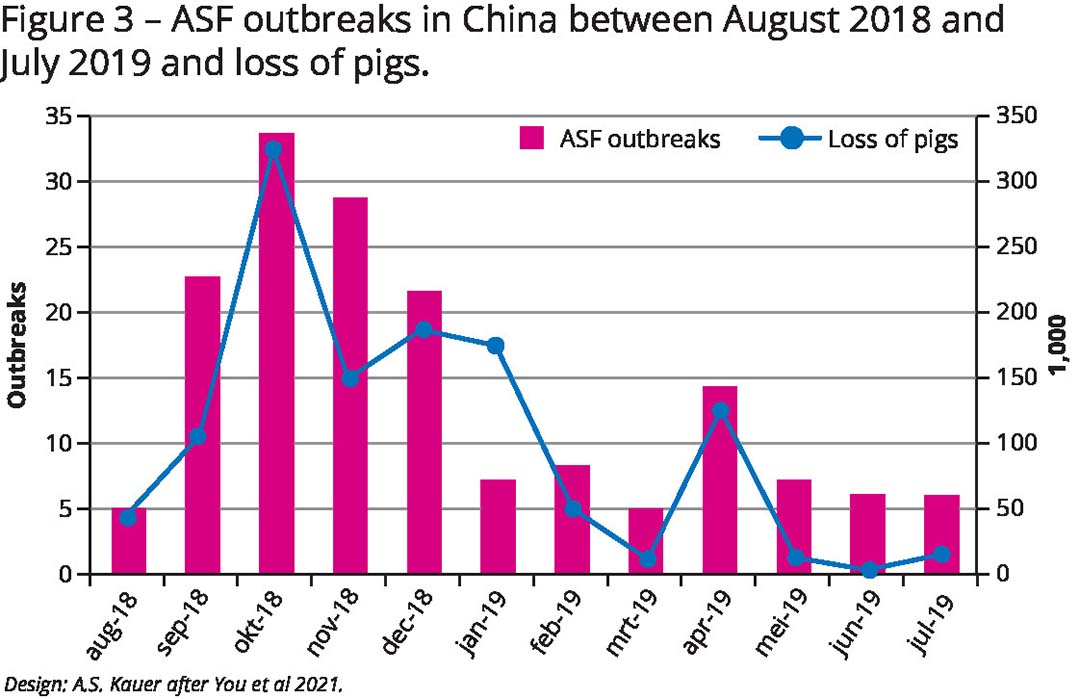

According to official government figures, a total of 162 ASF outbreaks had occurred by July 2019 (Figure 3). The virus infection had killed 13,355 animals and 1.2 million pigs had been culled to prevent the disease from spreading further.

Reported figures do not reflect reality

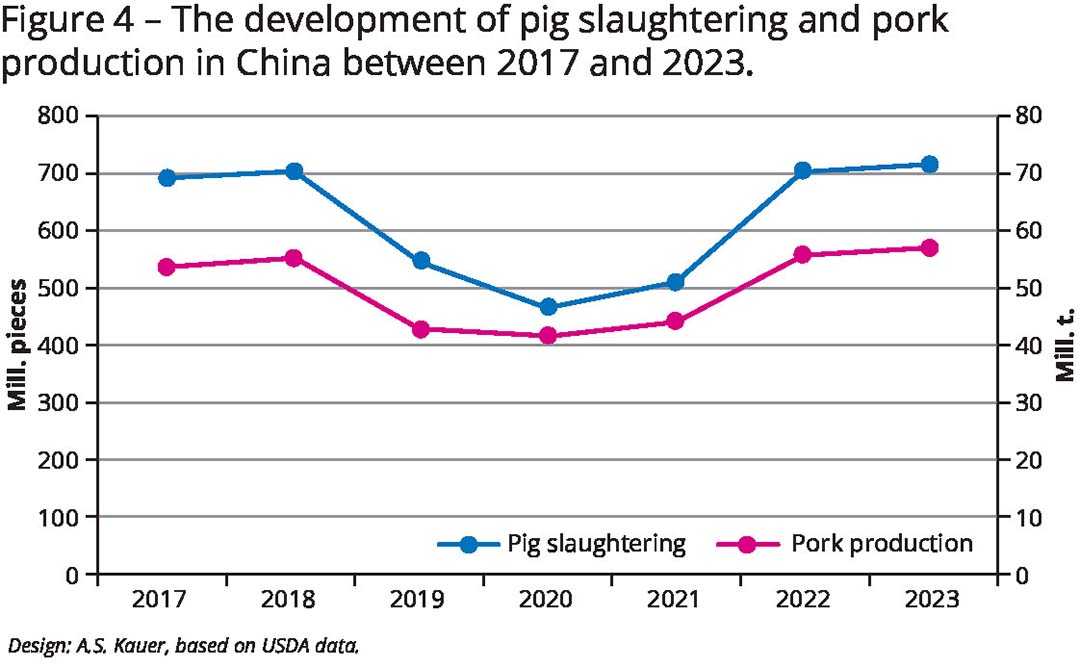

However, the reported figures do not reflect reality because they cannot be paralleled with the decline in slaughter numbers and pig meat production (Figure 4). Estimates from representatives of the slaughter companies assumed that 150 to 200 million pigs and sows died from the infection or were culled. This figure is almost identical to the USDA estimates. A paper by Shibing You of Wuhan University, China, in 2021 pointed out that the number of outbreaks was also far higher than the officially stated cases.

Although the figure for outbreaks in larger breeding and fattening facilities may be correct, the disease has probably also infected thousands of small flocks without these and the dead animals appearing in the statistics. Until the outbreak began, around 95% of pigs were still kept in herds with fewer than 500 places. The majority of pig losses are likely to have occurred here because the hygiene standard on these farms was low and no vaccine was available to prevent a further spread.

Insufficient compensation for monetary losses

In view of the impact on meat supply, the government took decisive action and not only cleared the infected herds, but also preventively culled all herds in the vicinity of an infected farm. As a result, many of the smaller farmers gave up sow rearing and pig fattening because there was insufficient compensation for the monetary losses incurred, which would, however, have been necessary to build up new herds. Because larger breeding herds were also affected, there was a shortage of piglets after the epidemic gradually subsided. As shown in the following article, the government tried to close this gap by importing large numbers of breeding sows.

Massive reduction of pig inventories

The massive reduction of pig inventories and the associated financial losses not only for producers, but also for upstream and downstream companies and for the economy as a whole, which were estimated to total US $ 111.2 billion, resulted in drastic changes in pig farming and pork production.

In order to prevent a comparable outbreak of the disease in future, the number of small farms was drastically reduced because they posed too high a risk. However, as the growing demand for pork was to be met in the long term without dependence on imports from abroad, investments were and are being made in large-scale piglet production and fattening facilities, both by private companies and the state. Some of these facilities have several tens of thousands of places for breeding sows or finishing pigs. The largest facility was built in Ezhou, Hubei province. It can produce 1.2 million slaughter pigs per year.

Economic reform

The first large-scale facilities were built during the presidency of Deng Xiaoping, who, due to the catastrophic economic situation at the end of the Mao Zedong era, initiated an economic reform and market liberalisation from 1978 onwards, which very quickly led to an economic revival of the country and improved living conditions for the population. Some of today’s leading companies in pig breeding and pork production emerged in the 1980s and early 1990s as a result of this change in strategy (Table 3). They are often vertically integrated.

Although the large-scale facilities, which for epidemiological reasons were often erected in remote locations, have significantly improved the supply of pork to the population, they have exacerbated the economic problems in the villages because a large number of small farms have been banned from pig production.

Their herds were rigorously culled during the ASF epidemic. This escalated one of China’s core problems that has not yet been solved, namely the dichotomy between the increasing urbanisation and the decline of rural areas. It has led to a mass migration problem, as around 270 million so-called peasant labourers are flocking to the cities in search of labour and income to feed their families left behind in the villages.

Beef – growing supply deficit

Table 1 already showed that the consumption of beef has risen continuously since 2017 and reached a volume of 10.9 million tons in 2023. However, because domestic production increased only slightly and even decreased by almost 700,000 tons in 2019 and 2020, the supply deficit increased from around 1 million tons to 3.5 million tons in the period under review. The significant decline in production in 2019 and 2020 was a consequence of the strict lockdown of entire cities, limited transport options and partial closure of slaughterhouses during the Covid-19 outbreak.

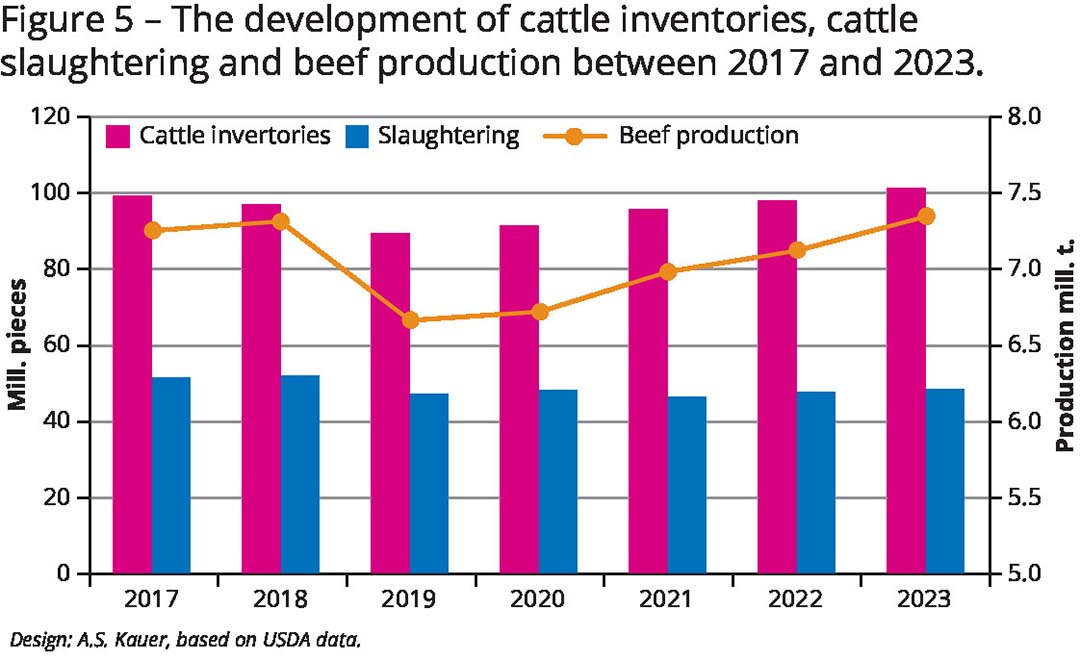

Figure 5 shows that cattle numbers fell by 10 million head between 2017 and 2019 and only gradually recovered. In 2022, they were still below the 2017 level and only reached a provisional peak of 101.5 million head in 2023. At the same time, slaughter numbers fell by 4 million head, and in 2023 they were still 5.5% below the 2017 figure, which indicates that it was not possible to provide sufficient cattle ready for slaughter due to the restocking with young animals.

Reasons for higher beef consumption

The increase in beef consumption is surprising at first glance. However, it can be explained by consumers’ reluctance to buy pork due to the ASF outbreaks and the extreme price increase, which resulted in government support measures because otherwise consumption would have fallen even more sharply.

There is another reason for the higher beef consumption. With the rising incomes of some consumer groups in urban centres, interest in beef has grown because eating it is also seen as a status symbol. As domestic production was unable to meet demand, increasing imports were necessary. The follow-up article will look into that in more detail.

Poultry meat – parallel increase

In contrast to the other 2 meat types, the supply of poultry meat to the population could be met by expanding production despite the rapid increase in demand (Table 1). The fast growth of the domestic consumption during the ASF outbreaks and the Covid-19 epidemic from 11.6 million tons to almost 16 million tons between 2018 and 2020 was offset by an equal increase in production.

With the fading of ASF outbreaks and the lifting of restrictions which had been effective during the Covid-19 epidemic, consumption and production fell slightly, partly because consumers returned to pork and partly due to import restrictions on grandparent stock for broilers. The supply of “white” broiler meat, which is increasingly favoured over “yellow meat” (i.e. poultry meat produced by small and medium-sized farm and sold on wet markets) is highly dependent on the import of genetics.

No easing of restrictions

As there was an outbreak of avian influenza (AI) in some supplier countries, including the USA, imports were strictly controlled and made dependent on prior PCR tests. Although higher imports of grandparent stock were permitted from 2022 onwards, it was not possible to supply sufficient numbers of broiler chicks to maintain production volumes. In view of a new wave of outbreaks in the USA since October 2023, it is unlikely that there will be a significant easing of restrictions in 2024.

No comparable performance

Although China has developed own hybrid lines and released for the market in 2021, they have not yet achieved comparable performance in terms of growing period and feed conversion as the imported hybrid lines. China will therefore have to continue importing foreign genetics in order to counter the trend towards white broiler meat among consumers.

Summary and prospects

The preceding analysis could show the remarkable dynamics in Chinese meat production and consumption between 2017 and 2023. It is obvious that the development was determined by the almost parallel outbreaks of ASF and Covid-19. That resulted in sharp declines in cattle and pig inventories and meat production. It was only after the ASF outbreaks subsided and the Covid-19 restrictions were lifted that there was a recovery.

In contrast, the poultry industry was able to meet the sharp rise in demand for poultry meat between 2018 and 2020 by expanding production. There was only a decline in production from 2021 onwards because imports of grandparent stock for broiler lines were severely restricted due to the outbreak of avian influenza in several supplier countries, resulting in a shortage of broiler chicks.

Meat production will rise

It can be assumed that meat production will rise considerably in the coming decade as demand increases. In its Agricultural Outlook, the OECD-FAO estimates that the production of pork will increase by 5.0%, beef by 4.2% and poultry meat by 6.7% until 2030. New technologies will be applied in order to catch up with the production output of the leading countries in America and the EU.

Prevention of epidemics

That will only succeed if epidemics of highly infectious diseases, such as ASF and AI, can be prevented. That will be associated with a further sectoral concentration in production, small farms will give up production due to a lack of competitiveness and large farms will increasingly take over shares in total production. The change is justified not only by lower unit costs, but also by higher hygiene standards on the farms. However, the leadership of China’s communist party has not yet come up with a concept for solving the problem of the dichotomy between increasing urbanisation and the decline of rural areas, where more than half of the population still lives.