What does science say about mRNA vaccines for pigs?

In a fast-changing world, novel technology can prove to be exciting and the next best thing. However, novel technologies may equally be a source of drawbacks that would only become visible at a later stage. mRNA vaccines have been welcomed during Covid-19, but also quite a lot of questions were asked about the pace of the developments. What does this all mean for the swine industry? Time to delve into the technology behind mRNA vaccination.

Any discussion about mRNA vaccines should be preceded by a decent biology lesson, otherwise an interested reader might well get lost before he or she even got started. After all, the article will delve deeply into the heart of all living creatures.

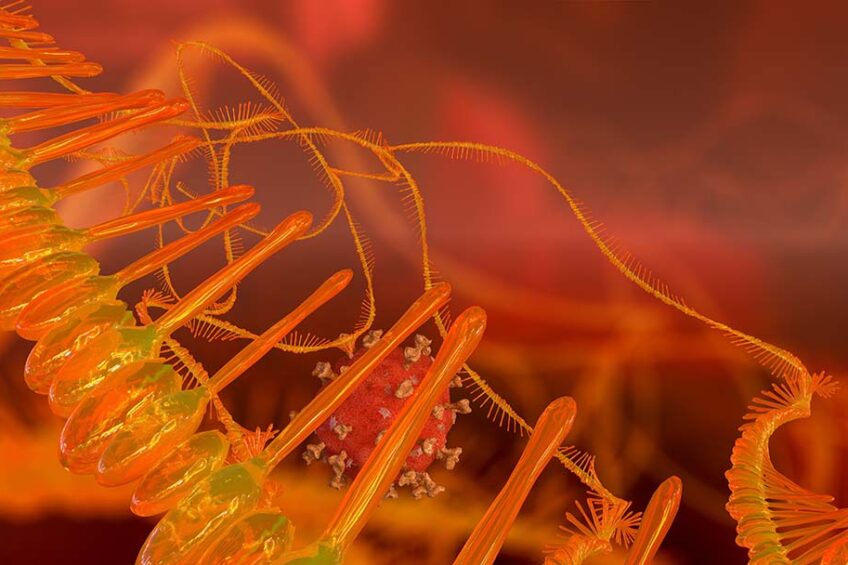

First things first – all living beings are built up from desoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) – the biological archive, bearer of all hereditary characteristics. Built up from base pairs, DNA is known for the double helix, and it is normally well tucked away well protected in host cells.

Its namesake, ribonucleic acid (RNA) is formed when functions need to be happening. This single strain contains partial copies of the DNA; these copies are necessary to code, transfer, convey and express genes, to eventually create proteins for the carrying out of certain functions. RNA can occur in various forms – one of them, and arguably the most well-known one is “messenger-RNA (mRNA).” mRNA is used as coding molecule during the translation and transcription from DNA to protein.

This mRNA forms the basis of a novel generation of vaccines. How this exactly works in detail is best explained by Dr Michael Roof, chief technology officer vaccines, diagnostics and immunotherapeutics at Iowa State University in the United States.

What are mRNA vaccines exactly – how do they work on a microbiological level?

Dr Michael Roof: “Within a normal host cell, the cell uses DNA as a template to make RNA, and the RNA is a template or “recipe” that the cell uses to make protein. mRNA vaccines provide the cell directly with mRNA of a desired vaccine target and this gets into the normal protein manufacture process to produce the desired vaccine antigens by the cell. It is important to know that mRNA has a short half life and so it gets naturally degraded by the cell within minutes or hours.

“For Covid vaccines in humans there were mainly 2 types of vaccines used. The first example uses viral vectors (for example adenovirus) to carry and deliver the desired Covid sequence into the cell which then made the subsequent protein target. Examples of this type of technology were the vaccines from Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca.

“The second type of vaccines were the mRNA vaccines in which synthetic RNA was injected directly into the cell and used to proteins relevant for immunisation. Examples of these vaccines were those manufactured by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna.

“There is research underway by a variety of investigators and companies to produce a self-amplifying mRNA vaccine. In this case the RNA template encodes both the antigen of interest gene as well as viral replicase genes to increase the amount of mRNA in the cell.”

How/when was the technology developed?

“The technology to use DNA or RNA for immunisation has been known and described for over 2 decades. Because of the short half-life or short stability of mRNA, the technology has only recently become commercially viable. RNA has a half-life that ranges from minutes to hours and so is naturally degraded within a cell.

“2 main advancements have allowed for the commercial success of recent mRNA vaccines. First was the discovery and use of modified nucleotides, which were more stable and increased the stability of mRNA. Secondly technology advancements in liposomes and nanoparticle technology also increased stability and provided advancements in vaccine delivery.”

Where is the pig industry when it comes to mRNA vaccines? What diseases might be tackled at this moment and in what countries/ parts of the world is it allowed? What is to be expected?

“Within the US animal health there are no mRNA vaccines such as Moderna/Pfizer sold at this time. Merck Animal Health does have a product marketed as Sequivity that uses a defective Venezuela Equine Encephalitis virus to deliver RNA into a cell and produce a targeted immune response. The Center for Veterinary Biologics (CVB) has characterised this as an RNA particle in their regulatory assessment.

“There are many companies looking at mRNA vaccines and their applications in animal health. Influenza is a common target under investigation as the HA (haemagglutinin) is a known protective immunogen and has applications across many species. The most promising disease targets are viral with small genomes. Bacterial diseases (big genome and multiple virulence factors) and larger virus (ASFv) remain viable but more challenging targets.”

Does EU legislation provide any obstacle for the introduction of this type of vaccines in Europe?

“Although the European regulatory process is different than that of the USDA/CVB, there are no specific regulations that prevent the consideration of RNA vaccines. Any new vaccine or vaccine technology would need to fulfil the regulatory guidelines defined by EMEA to ensure safety and efficacious use.” (see also box)

What lessons did the pig industry learn from the human Covid-19 vaccines?

“I think in some ways, animal health was ahead of the human industry in that we have products and processes in place to handle frozen vaccine product and product distribution.

“Secondly, veterinarians and the industry have a good understanding of herd immunity and the importance getting broad immunisation within a population.

“Where I think animal health can learn from Covid in are around the political and emotional perceptions related to vaccine use. Historically, society has accepted and benefited from vaccines as important to human health. Diseases such as smallpox, polio and others have been eliminated and yet today there is increased vaccine hesitancy for a variety of reasons.

“Within animal health we now see state legislators discussing laws and legislative policy potentially regulating vaccine use in animals and so the animal health industry needs to be engaged to ensure they have the tools available to ensure food safety, animal welfare, and disease control.

“In addition, it is important to note that vaccines are already well regulated by the USDA and CVB who have the experts and competency to assess animal safety, animal efficacy, environmental impacts and human impact. Additional regulation not only isn’t helpful but creates complications and confusion in compliance and could have import/export ramifications.”

The body has a variety of nuclease and RNAse enzymes which chew-up and destroy nucleotides to ensure no over-expression

Especially around Covid, there have been a lot of negative comments on mRNA vaccines. Are there any mRNA vaccine myths that you feel need busting? And are there areas around mRNA vaccines you feel more research would be good?

“In my opinion there are 2 main challenges in vaccine perception that need to be addressed. First is the issue surrounding mRNA integrating into the host and creating some “Frankenstein” situation. RNA and mRNA are incredibly unstable and so have a half-life of seconds, minutes, or hours… But certainly do not incorporate into the host genome or persist for long periods of time. The body has a variety of nuclease and RNAse enzymes which chew-up and destroy nucleotides to ensure no over-expression.

“Secondly there are issues of what to “expect” as a result of vaccination. In both human and animal health, there is a lot of variability of how individuals respond to a vaccine. Some may experience nearly completed protection and others may have partial protection but get less sick than if not vaccinated.

“This is normal and demonstrates that immunisation is a complex issue impacted by the host, the environment, and the specific disease. In general vaccines reduce the severity of clinical disease and often reduce the level of pathogen. Few vaccines provide sterilising immunity. This does not justify or suggest there is not benefit in vaccination.

“If and when a majority of a herd or population is vaccinated, the long-term benefits are generally shorter disease prevalence, less severe disease, less disease treatment and reduced or slower disease change.

“The opposite is also true in that in partially immunised populations you see more frequent disease and accelerated disease change. As an example, as humans more frequently decline childhood immunisations, we see now the re-emergence of diseases such as whooping cough, measles and chickenpox. Vaccines are not magic but they do provide both individual and population benefits.”

Some consumers have expressed worries about possible effects of the use of mRNA vaccines on meat quality. What would you tell those consumers?

“The simple and easy answer is that mRNA vaccines do not integrate into the host genome. mRNA has a half-life that is very short and so these get degraded very quickly. So they pose no safety issue nor food consumption issue.”