Free farrowing and crushing: what actually happens?

With free farrowing likely to be at the doorstep for the European Union, it is time to develop new housing systems. But wait! Will piglets get crushed now? Time to zoom in: if piglets die in free farrowing systems, when does that happen, and where, why, how, etc.? A research team in Italy used the latest technology – and gave three take-home messages.

The big debate in the European Parliament has been postponed various times now. Yet it is commonly accepted that one day it is going to happen, that “Brussels” will send out the message that farrowing crates are about to be phased out in pig production. Some countries already banned crates, like Switzerland for instance. Others are in the process to do so, like Germany and Austria. In fact, most farms, countries and equipment companies are seriously considering future steps. Some do that with enthusiasm, others may prefer not to think about it too much. After all, it will mean a major change in animal husbandry and how about the piglets’ lives? Isn’t the industry heading for major disaster with all these extra piglets being crushed?

In that process, it struck researchers at the University of Turin in Italy, that one aspect of the entire discussion hadn’t been receiving a lot of attention. As researcher Dr Maria Costanza Galli formulated it at the recently held European Symposium for Porcine Health Management (ESPHM) in Switzerland: “There is still a lack of in-depth knowledge of the dynamics associated with crushing events in systems without permanent confinement, especially with hyper-prolific sows, which are now widely used in pig farming, but poorly selected for their maternal behaviour and for good piglet viability.”

In other words: the team wished to quantify the process of sows with their piglets. That meant a good few hours in the pig house, with sensors, cameras – and no intervention. It may not always have been a pretty sight, but it led to valuable insights.

The trial

The team observed 68 hyper-prolific sows and litters in the trial. The sows were held in pens of 7.2 m2 of which the sow had 4.68 m2 at her disposal. There was temporary crating possible for the first seven days post-partum; the pens were equipped with three farrowing rails and a creep area of 1.3 m2. The team studied available footage from the moment crates were removed.

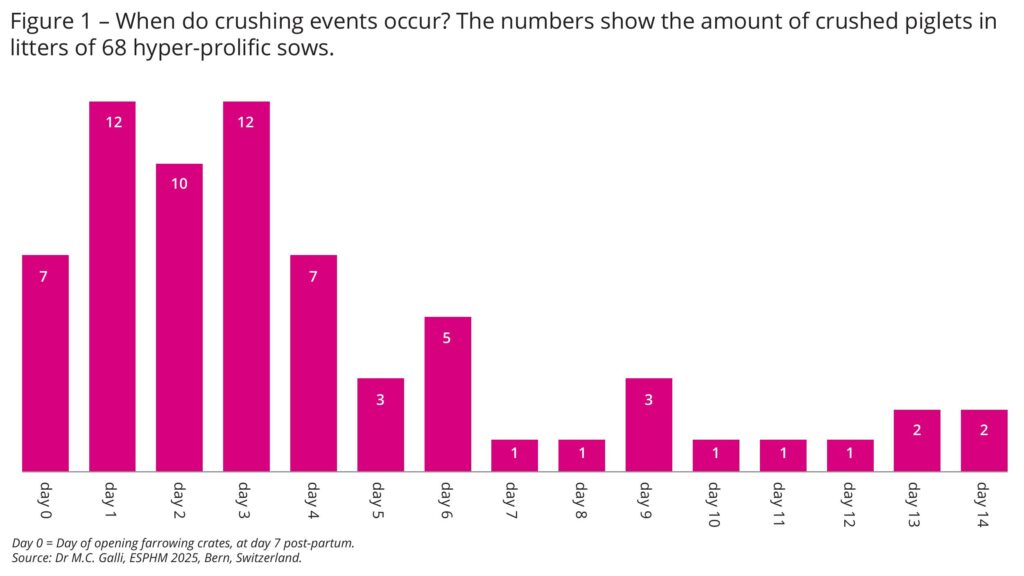

The research team studied in total 65 “crushing events,” which happened in 56 litters. In total 68 piglets got crushed. Every time, they watched the two minutes before it happened – and collected data like the number of piglets, their condition, the date and time of the events, the piglets’ activity (sleeping, suckling, being active) as well as the sows’ activity and how they changed their posture (e.g. rolling, sternal or lateral lying down, sitting). In addition, environmental and nest temperature were also noted in case of crushing.

Results

The team investigated all kinds of questions, e.g. in what season the most crushing occurred, where in the pen the most crushing would occur, what kinds of sow posture changes were the most lethal. In 18% of the cases, the crushed piglets were classified as unwell, for instance undersized, lame or starved. In other words, in 82% of the cases, the sow played a role. In a few cases, the outcomes were remarkable.

When taking the day of “opening” the crate as day 0, the majority of crushed piglets happened on day 1 (12) and day 3 (12). Nevertheless, crushing happened every day, up until day 14 – as is shown in Figure 1.

In terms of the most frequent posture changes, the team concluded that “crushing due to the sow descending from standing to a lateral position is not a common event.” In fact, the team said, “76% of crushing events of healthy piglets occurred because the sow rolled from ventral to lateral lying.” The team also mentioned that in 73% of the healthy piglets dying, the piglets had been sleeping.

All in all, Dr Galli and her team reached three take-home messages how to reduce piglet mortality in free farrowing pens.

Attracting piglets from the sow area

Attracting piglets from the sow area

The team pointed to “poor utilisation of the nest area” as a key aspect of piglets being crushed. Showing images of piglets lying spread out over the pen floor, also close to their mothers, it became clear that warmer ambient temperatures cause a problem. As soon as in summer the temperature of the piglet nest is equal to the ambient temperature, the piglets may not be tempted to look for the nest to lay down. So, the team said, it would be vital to promote greater nest utilisation, and to increase the temperature gradient between nest and pen areas. In winter and mid-seasons this is normally not much of an effort with warmer mats and a heat lamp. In summer months, however, that may require some proper thinking. A light source, the team found, attracted piglets to the creep area.

Limiting the sows’ rolling behaviour

Limiting the sows’ rolling behaviour

In addition, an option could be to limit the sows’ rolling behaviour. Interestingly, Dr Galli showed an example of gently doing so, by connecting “plastic mushrooms” to the slatted floor, orange mushroom-style balls which tactfully guide the sow where to lie down. The method, she explained, has only been reviewed once, in a British scientific review, but it exhibited the lowest mortality rate.

Increasing maternal responsiveness

Increasing maternal responsiveness

Thirdly, the team said, the increase of maternal responsiveness could be an option. In correspondence with Pig Progress, Dr Galli explained, “Maternal responsiveness in sows refers to the behavioural and physiological reactions of the mother to her piglets, particularly in response to distress signals such as vocalisations. Responsive sows are more likely to attend to vocalisations, adjust their posture carefully, and exhibit protective behaviours, thereby reducing piglet mortality.”

She continued to say, “However, there is considerable variation among individuals in maternal behaviour. While some sows consistently respond to piglet distress by standing or repositioning, others show minimal or no reaction, increasing the risk of piglet loss.” Improving maternal responsiveness can be achieved through both genetic and environmental approaches, she explained. She said, “Genetic selection for maternal traits – such as responsiveness to piglet vocalisations and cautious posture changes – can enhance sow behaviour over generations. Additionally, providing environmental enrichment (e.g., nesting material before farrowing) and using farrowing systems that allow greater freedom of movement can support natural maternal behaviours and reduce stress, further promoting positive sow-piglet interactions.”