Pig claws via high-speed X-ray cameras

It is interesting to understand how pig claws interact with hard surfaces technically unknown to them. A research institute at the Leipzig University, Germany captures all pig movement on camera to follow and analyse every step they take. Watch the videos below…

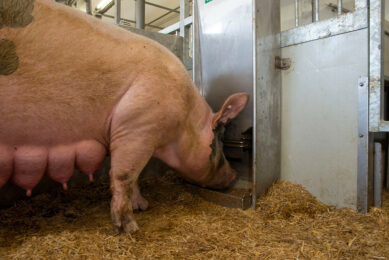

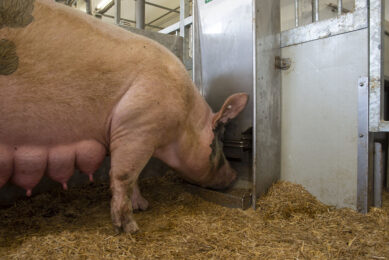

Sows in modern intensive housing environments face a substantial threat from claw lesions. The risk of the claw developing a painful and ultimately devastating lesion is based on its interaction with the flooring surface, overcrowded conditions and aggressive social behaviour. The majority of claw lesions have a strong biomechanical component in their development (pathogenesis). Mechanical impact is either the direct (primary) cause of lesions or promotes the progression of a lesion caused primarily by other factors such as metabolic disorders, mineral imbalances/deficiencies or local inflammation.

One of the most critical factors contributing to the development of claw lesions in today’s swine operations are hard flooring systems. The pig’s foot is anatomically designed for a soft, variable, uneven surface where weight bearing by the two main claws is significantly supported by weight bearing of the two dew claws. When the pig is placed on concrete, the mechanics of the foot and how it interacts with the flooring surface is being changed. The result is increased production of horn of inferior quality, disruption of normal horn formation or mechanical damage to the tissue and subsequent inflammation.

Once the sow experiences lameness and pain due to a claw lesion, her performance including her reproductive potential is severely compromised and she may need to be removed from the herd.

Through research studies, genetic improvement and management techniques, swine producers have the opportunity to reduce, and even prevent, the painful claw lesions that decrease not only productivity of sows but also their well-being.

Video: Highspeed videography – motion analysis

Research into pig lameness

One area of research at the Institute of Anatomy, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Leipzig University focuses on structure, biomechanics and fluoroscopic motion analysis of the bovine and porcine claw and on the development (pathogenesis) of claw lesions. The institute employs a broad spectrum of methods including gross anatomical dissection, microscopy, immunohistochemistry, electron microscopy and in vitro studies in its cell culture lab.

The work on pig claws, sows in particular, started about three years ago with studies on the histopathology of claw lesions. Histopathology, the microscopic examination of pathological altered tissue, facilitates an understanding of the relationship between the cause, nature, stage and severity of claw lesions. Knowledge of the origin, the causes of lesions, the mechanisms behind their development and their progression over time helps to develop preventive measures and improve management in our herds to reduce the incidence of lesions and improve the well-being of the pigs.

Figure 1 – Development of a painful lesion.

Since August 2013, the Veterinary Faculty runs a bi-planar fluoroscopic gait lab, based at the Institute of Veterinary Anatomy, suited for small and large animals, using state-of-the-art high speed fluoroscopic kinematography to study locomotion in healthy and diseased animals. Bi-planar fluoroscopic kinematography is the technique of choice when assessing joint kinematics in live animals during locomotion. Both, marker less and marker based (small implanted metal beads) tracking of the bones are available, allowing application of the technique in basic and clinical research.

The FluoKin unit enables precise studies and analysis on claw floor interaction in live animals. Gathering more information on this interaction will be of paramount importance for improving the claw health in pigs.

Rudi, first pig on the treadmill in the FluoKin Lab

In order to establish the fluoroscopic analysis of pig limbs and claws we performed a pilot study on a small number of pigs (two male fatteners and two young adult sows). Initially, we trained our first male rearing pig ‘Rudi’ to walk on the treadmill. Rudi managed this task surprisingly well. It took only one 30 minute session to train him to walk with his harness on a leash on the treadmill.

Video: Fluoroscopic motion analysis

We took high speed X-ray videos with 550 frames /sec of his fore and hind limbs focusing on the carpus/hook region and on the pedal bones and joint inside the claw capsule. Three other pigs followed Rudi, including two adult sows (160 kg). We were able to get good quality high speed videos of the joints and claws of all pigs. These data have been analysed visually. Precise 3-dimensional reconstruction and measurements of position of joints and the pedal bone inside the claw capsule will follow. So far, the studies demonstrate that the dew claws in all pigs examined were not in contact with the floor, a hard rubber mat on the treadmill.

The dew claws did not contribute to weight bearing with the consequence that the whole body weight was loaded on the main claws exclusively. This represents a high mechanical challenge and increases the risk of claw tissue damage. There is a clearly visible significant concussion in the distal limb during footing. During the main footing phase the pedal bone compresses the digital cushion at the rear end of the claw and sinks downward.

Another critical phase is the roll over just before taking off the claw from the ground. Here the tip of the toe, where there are no protecting fat cushions, is exposed to high mechanical stress.

Claw health in pigs

The FluoKin lab enables precise studies and analysis on claw floor interaction in live animals. Gathering more information on this interaction using different floor materials will be of paramount importance for improving the claw health in pigs.

The FluoKin analysis so far supports that balance of the sow’s foot is a critical area to address in the prevention of lameness and claw lesions. Claw trimming is one of the easiest and most practical things that can be done to prevent claw lesions and lameness. The majority of lesions observed have primarily mechanical causes or a strong mechanical component in their development.

Table 1 – Claw lesions in sows: causes.

Forces impacting on the claw tissues during locomotion, sudden stops, turns, jamming and pinching in slats etc., are all a result of the claw-floor-interaction that can now be visualised and analysed in the fluoroscopic lab. Any mechanical interaction between claw and environment has an impact on the sensitive living interior structures of the claw. Alterations in the claw ranged from stimulation of horn production (hyperkeratosis) leading to a thickening of the claw horn to disruption of horn production or even complete separation within the claw capsule. Even minor cracks will increase over time while exposed to the permanent challenges and eventually develop into a penetrating separation of the horn capsule. The living dermis beneath is exposed to the environment and gets infected. Inflammation is the consequence. A painful lesion develops with lameness as the clinical visible sign.

The overarching future aim of these studies combining pathohistology and state-of-the-art fluoroscopic analysis in live animals is to better understand development of lesions and their progress over time. Based on this knowledge it is possible to provide guidance for preventive measures, focusing on management of the sow’s environment, namely the floor, and on claw trimming to improve the well-being of sows and thereby their longevity and economic sustainability.

More information: www.fluokin.de. The pilot study was supported by Zinpro, Eden Prairie, MN, USA.