Health management key in all phases of a sow’s life

Sow health is a cornerstone of a pig farm. The breeding cycle must be planned, maintained and prioritised. In this cycle, health problems are never far off. Which health problems occur during modern sow management – and how can they be avoided?

By Dr John Carr and Mark Howells, Howells Veterinary Services, Easingwold, Yorkshire, United Kingdom

Too much emphasis is placed on the piglets born and numbers weaned. The number of weaned sows is actually more important for the farm and the breeding team than the number of piglets weaned. The number of weaned sows determines that the next batch breeding target is achieved. Weaning 240 piglets this batch is less than important than consistently weaning 240 batch after batch for the whole year.

To maximise the maintenance of the sow’s heath, the farm’s health team must plan the farm and then organise the farm around the agreed plan. This requires considerable attention to the farm’s layout and potential. Once the plan is agreed, pig farming becomes much simpler. It is vital to remove variation between batches.

The farm plan is generally centred around the batch farrowing number. The number of sows or space in finishing cannot be used, as these requirements vary between batches with the seasons.

The term which needs to be understood carefully by the farm team is the term ‘minimum’. The adoption of this term, with regard to breeding, throws into question many of the current well held beliefs. Numbers relating to ‘sow’ become irrelevant. Thus ‘pigs per sow per year’, ‘none productive sow days’ and even ‘farrowing rate’ become incidental measurements, which by themselves have no direct impact upon the profitability of the farm. It follows that to farm the plan, the review of sow health then must focus on the reasons why sows fail to be part of the next batch. Disruption may occur if:

1. Sows become ill and loose their piglets;

2. Sows become ill and die;

3. Sows are be culled or euthanised.

1. Illness & abortion

Sows may become ill and subsequently loose their piglets because they develop a high temperature (‘pyrexia’). The pyrexia engenders prostaglandin, which in turn leads to regression of the corpora lutea (‘CL’) in the ovaries. Destruction of the corpora lutea causes progesterone production to plummet and abortion follows. Health issues which the farm health team needs to be aware of, are:

Erysipelas

Erysipelas is significant and ubiquitous; some 25% of normal pigs carry Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae in their tonsils. Vaccination has been remarkably successful at controlling this pathogen.

Swine influenza virus

This virus can be brought onto a pig unit by staff. For example, the H1N1 2009 influenza virus (Mexican Flu) readily transmits from people to pigs but rarely the other way around. Influenza is classically thought of as a short term problem, but on large farms and outdoor units negative subpopulations can be a problem and vaccination may be required to break the cycle. Unfortunately vaccines do not confer lifelong immunity and need to be repeated every six months.

PRRS virus

Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS) virus is evolving and causing more clinical problems in the adult herd in Europe. In North America, abortion storms are common when a new strain of PRRSv first enters a farm. As the European PRRSv evolves it is starting to be associated with more abortion issues.

Other abortion-related disorders:

Opinion is divided about leptospirosis: There is a 50:50 split among advisors as to whether it is a cause of problems. Where rodents are a problem, leptospirosis can certainly be associated with serious clinical issues and result in farrowing rates of 60% and high culling rates of sows associated with infertility.

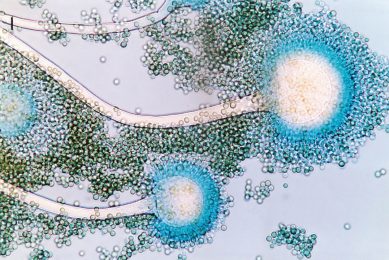

Mycotoxiciosis can cause abortion and straw can be a significant source. Mouldy feed, especially zearalenone, can result in reproductive problems resulting in increased culling of sows and gilts. Note mycotoxins also appear to combine with each other reducing the required toxic dose. This can make analysis extremely difficult.

2. Illness & death

The major causes of sow mortality on normal farms are associated with abdominal catastrophe. Any variation is feeding routines can cause excitement in a few sows which bolt their water and then their feed. Hypermotility of the intestines leads to unstability and a torsion may occur.

Ascending urinary infections (pyelonephritis) used to be a significant cause of sow mortality – especially around farrowing or shortly after breeding. Increased awareness of water requirements has solved this problem on most pig farms.

Feeding gestating sows once in the afternoon reduces urinary tract disorders because it encourages them to rise and urinate in the afternoon and evening. Feeding once a day also trains the stomach to accept larger volumes of food, enabling hyperprofilic lactating sows to eat 12-14 kg dry lactation feed at peak lactation.

3. Culling and euthanising

Numerous studies have looked at sow culling. Figure 3 shows a typical breakdown. These studies are usually flawed because the opinion of the stockperson at the time is taken as ‘fact’. In reality, a sow may have to leave the farm for a variety of reasons, but the stated cause is the one causing the stockperson least grief with the owner.

For example, a sow culled in week 15 of gestation may be recorded as being lame or having a bad foot rather than being found ‘not in pig’ at such a late stage – as this is more acceptable to the farm team.

No sow should be culled until a fresh pregnant gilt is available to replace her. Note the wording – pregnant gilt.

When can this be achieved? Certainly not at weaning which is the ‘normal’ culling time on many farms. Culling needs to be planned and coordinated.

When a sow leaves the farm it should be a time for celebration. The sow at sixth and seventh parities which has successfully reared some 600 kg of weaned pigs over her lifetime is a success. She has cycled promptly after weaning without the need for a repeat mating. There is a pregnant gilt to replace her. This is a ‘positive’ culling event. This sow has been a good employee, an excellent member of the farm team. Unfortunately in most herds, the majority are ‘bad’ culls. Can they be considered animals who have failed or did we fail them?

Loose housing regulations

It is interesting to see what the group housing regulations in the EU and elsewhere are going to make with regard to sow health and body condition.

Sows are kept in suitably designed stalls until their pregnancy check in most of the European Union. A few countries have restricted this time period.

It is essential to ensure that sows and gilts are not bullied and ridden by sows in heat; if a large bully sow rides a smaller gilt, she may become lame and even develop life threatening injuries. Careful management of sow size and groupings are required and increasing the group size through batching can help to reduce problems.

The management of sow body condition is much more difficult in loose housed situations. This is critical now that large litter sizes are ‘the norm’ – the large lactation feed intakes needed to sustain a high lactational output which can only be achieved with careful control of sow body condition.

Slatted/ no bedding/ bedding?

The EU now restricted dry sow stalls and the amount of the floor which can be slatted. The designers of buildings now need to predict defecation areas for the sows.

This is an extremely common failure in building design. Poor building design results in large amounts of faeces remaining in the sow’s environment. Sows are then subjected to more faecal contamination (feet, udder and genital tract) and have to sleep in wet and cold environments.

Their feet become soft and lameness more common.

The floors may become slippery, which can result in trauma to the upper joint, rendering the sow unable to rise. This is often fatal.

Changes?

To conclude, the pathogens and disorders which result in a deterioration in sow health will not significantly alter with the change in legislation. Poor management of loose housed sows is likely to increase problems associated with the environment (lameness and general hygiene). Loose housing is not a panacea for sow health, it only changes the landscape.

Management practices which need addressing

Medicine management

* Don’t allow medicines to freeze in the fridge;

* Use a 40 mm needle to allow for an intramuscular injection with sows.

Contamination management

* Don’t use mouldy straw;

* Avoid feed getting mouldy – treat feed bins;

* Apply rodent control measures;

* Apply bird control measures;

* Adhere to feeding times;

* Feed in the afternoon once a day;

* Maintain adequate clean water supplies at all times.

Join 18,000+ subscribers

Subscribe to our newsletter to stay updated about all the need-to-know content in the pigsector, three times a week. Beheer

Beheer

WP Admin

WP Admin  Bewerk bericht

Bewerk bericht